Ask anyone who the world’s all-time richest person is and you’ll probably hear Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Gates or Warren Buffett – but that is of course, wrong.

His name was Mansa Musa and he was an African Muslim king, whose 4,000-mile trip to Mecca accompanied by a caravan of 60,000 people and thousands of servants, went down in history.

Musa was born in 1280, and Mansa means ‘Sultan’ in the native language of Mandinka spoken in the region. He came to the throne in 1312 and in his 25-year reign, the Kingdom of Mali expanded massively to include the current day nations of Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Guinea and the Ivory Coast.

Some historians believe that with an inflation-adjusted fortune, his wealth amounts to around $400 billion today. But, he was not just a rich man and sultan.

***

Mansa Kanku Musa took power in 1312 CE and inherited an already prosperous Mali kingdom; he would reign until 1337 CE. Mansa was the traditional Mali title meaning ‘king’ and Musa was the grand nephew of the founder Sundiata Keita. Mansa Musa gained the throne after his predecessor, Mansa Abu Bakr II, sailed out into the Atlantic with a large fleet of ships and was never seen again. Exploration’s loss was Mali’s gain, and Mansa Musa, nominated to rule while Abu Bakr II satisfied his curiosity as to what lay over the horizon, would become one of the greatest rulers in the entire history of Africa.

With an army numbering around 100,000 men, including an armoured cavalry corps of 10,000 horses, and with the talented general Saran Mandian, Mansa Musa was able to extend and maintain Mali’s vast empire, doubling its territory and making it second in size only to that of the Mongol Empire at the time. Mali controlled lands up to the Gambia and lower Senegal in the west; in the north, tribes were subdued along the whole length of the Western Sahara border region; in the east, control spread up to Gao on the Niger River and, to the south, the Bure region and the forests of what became known as the Gold Coast came under Mali oversight. This latter region was left semi-independent because gold production had always been much higher when more autonomy was granted there. The Mali Empire would never control such large territories under any of its subsequent rulers.

To better govern this vast expanse of land containing a multitude of tribes and ethnic groups, Mansa Musa divided his empire into provinces with each one ruled by a governor (farba) appointed personally by him. The administration was further improved with greater records kept and sent to the centralised government offices at Niani. The wealth of the state increased thanks to taxes on trade, the Mali-controlled copper and gold mines, and the imposition of tribute from conquered tribes.

Mansa Musa in Cairo

Mansa Musa, like many other devout Mali rulers before and after, set off for a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 CE, but when he arrived in Cairo in July of that year en route, he caused an absolute sensation. The Mali ruler’s camel caravan had crossed the Sahara and when he arrived in Egypt, even the Sultan was astounded by the wealth this West African king had brought with him. In some accounts, each of 100 camels carried 135 kilos (300 pounds) of gold dust while 500 slaves each brandished a 2.7 kilo (6 pounds) gold staff. In addition, there were hundreds of other camels loaded down with foodstuffs and textiles, horse riders waving the huge red and gold banners of the king, and an impressive human entourage of servants and officials that numbered in the tens of thousands. In an extreme gesture of largesse, Mansa Musa would give away so much gold and his entourage spend so much shopping in the markets of the city that the value of gold dinar in Cairo crashed by 20% (in relation to the silver dirham); it would take 12 years for the flooded gold market to recover.

THE KING OF MALI HAD GIVEN 50,000 GOLD DINARS TO THE SULTAN OF EGYPT MERELY AS A FIRST-MEETING GESTURE.

The merchants of Egypt, in particular, were delighted with all these naive tourists suddenly milling about their markets and they took full advantage, raising their prices and relieving the shoppers of their gold at any opportunity. Indeed, Mansa Musa and his people so overspent that they left the city in debt, a factor which contributed to later Egyptian investment within the Mali Empire so that the merchants could recoup some of the value of the goods they had given on credit.

The king of Mali had given 50,000 gold dinars to the sultan of Egypt merely as a first-meeting gesture. The sultan was rather ignoble in return and insisted that Mansa Musa kiss the ground in homage. In all other respects, though, this ruler from Africa’s mysterious interior was treated like the royalty he was, given a palace for his three-month stay, and lauded wherever he went. The Arab historian Al-Makrizi (1364-1442 CE) gives the following description of the king of Mali:

He was a young man with a brown skin, a pleasant face and good figure…His gifts amazed the eye with their beauty and splendour.

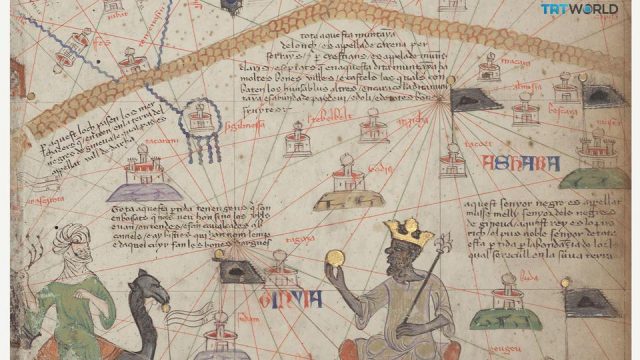

An indication of the impression Mansa Musa had made is that news of his Cairo visit eventually reached Europe. In Spain, a mapmaker was inspired to create Europe’s first detailed map of West Africa. Created c. 1375 CE, the map, part of the Catalan Atlas, has Mansa Musa sitting regally on a throne, wearing an impressive gold crown, and holding a golden staff in one hand and, somewhat gleefully, a huge nugget or orb of gold in the other. It was such tales of gold that would inspire later European explorers to brave disease, warlike tribes, and inhospitable terrain to find the fabled riches of Timbuktu, the golden city of the desert that nobody quite knew where to place on the map even in the 18th century CE.

After Cairo, Mansa Musa would travel on to Arabia where he purchased land and houses so that pilgrims from Mali who followed in his footsteps might have a place to stay. The king was inspired by the holy sites he saw there and on his return to Mali, he built a dazzling audience chamber at Niani and mosques at Gao and Timbuktu. These included the ‘great mosque’ in the latter city, also known as Djinguereber or Jingereber. The buildings were designed by the famous architect Ishak al-Tuedjin (d. 1346 CE and also a noted poet) from Andalusian Granada, who had been enticed from Cairo following Mansa Musa’s visit there – the inducement included 200 kilos (440 pounds) of gold, slaves, and a swathe of land along the Niger River. The mosque was completed by 1330 CE, and al-Tuedjin lived the rest of his life in Mali. A royal palace or madugu was built in the capital city and Timbuktu, along with fortification walls to protect the latter city against raids by the Tuareg, the nomads of the southern Sahara. Due to the lack of stone in the region, Mali buildings were typically constructed using beaten earth (banco) reinforced with wood which often sticks out in beams from the exterior surfaces.

Mansa Musa was also inspired by the universities he had seen on his pilgrimage, and he brought back to Mali both books and scholars. The king greatly encouraged Islamic learning, especially at Timbuktu, which, with its mosques, universities, and many Koranic schools, became not only the holiest city in the Sudan region of West Africa but also an internationally famous centre of culture and religious study. In addition, Mansa Musa sent native religious scholars to Fez in Morocco to learn what they could and then return to Mali as teachers. With these education links there were, too, diplomatic ones with Arab states, as well as the flow of investment into Mali, as Egyptian traders and others sought access to the lucrative movement of goods across West Africa.

Source: ancient.eu and trtworld.com