When it comes to loosening social mores, progress that isn’t made in private has often taken place onstage.

That was certainly the case at the Clam House, a Prohibition-era speakeasy in Harlem, where Gladys Bentley, one of the boldest performers of her era, held court.

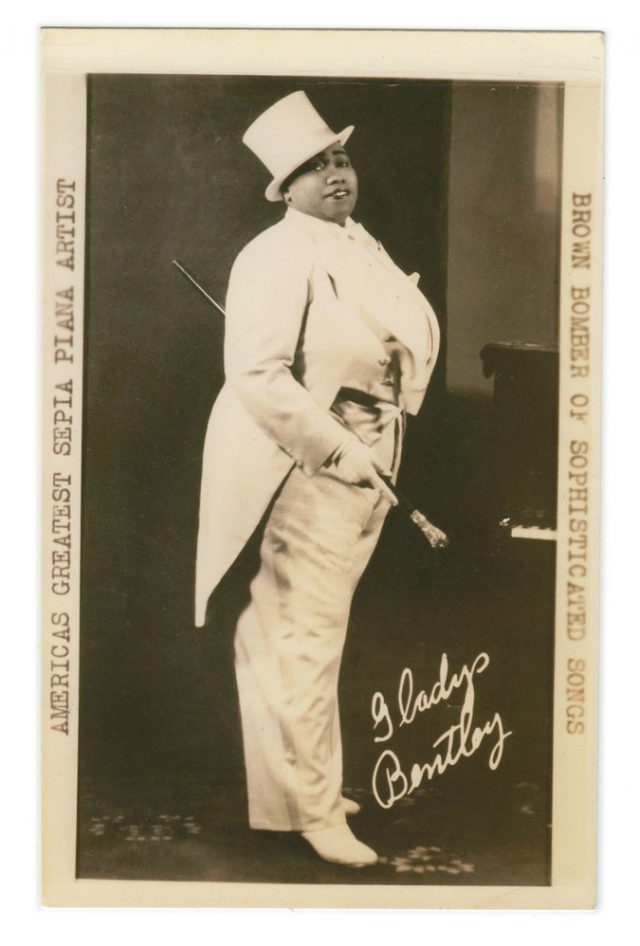

In her top hat and tuxedo, Bentley belted gender-bending original blues numbers and lewd parodies of popular songs, eventually becoming Harlem royalty. When not accompanying herself with a dazzling piano, the mightily built singer often swept through the audience, flirting with women in the crowd and soliciting dirty lyrics from them as she sang.

By the early 1930s, Bentley was Harlem’s most famous lesbian figure — a significant distinction, given that gay, lesbian and gender-defying writers and performers were flourishing during the Harlem Renaissance. For a time, she was among the best-known black entertainers in the United States.

Bentley sang her bawdy, bossy songs in a thunderous voice, dipping down into a froglike growl or curling upward into a wail. In his 1940 autobiography, Langston Hughes called her “an amazing exhibition of musical energy — a large, dark, masculine lady, whose feet pounded the floor while her fingers pounded the keyboard — a perfect piece of African sculpture, animated by her own rhythm.”

In a letter to Countee Cullen, the Harlem socialite Harold Jackmanwrote: “When Gladys sings ‘St. James Infirmary,’ it makes you weep your heart out.”

Indeed, Bentley knew her success was built on talent as much as notoriety. “The world has tramped to the doors of the places where I have performed to applaud my piano playing and song styling,” she wrote in a 1952 essay for Ebony. “Even though they knew me as a male impersonator, they still could appreciate my artistry as a performer.”

Bentley’s rise to fame demonstrated how liberated the Prohibition culture of the Harlem Renaissance had become, and how welcoming the blues tradition could be to gay expression. She often confronted male entitlement and sexual abuse in her lyrics, and declared her own sexual independence. This was, in fact, the continuation of a tradition begun by other singers of the early 20th century, particularly Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey and Lucille Bogan, who were some of the most vocal musician critics of patriarchy of their time.

But Bentley was the first prominent performer of her era to embrace a trans identity, implicating her body differently in these acts of musical defiance. (Throughout her life, Bentley used female pronouns to describe herself — at least in public.)

On a 1928 recording of her “Worried Blues,” for OKeh Records, Bentley sang: “What made you men folk treat us women like you do? / I don’t want no man that I got to give my money to.”

Between lines, she improvises vocal fills, uncannily mimicking a trumpet and hitting the notes spot on. On “How Much Can I Stand,” from later that year, she depicted an abusive relationship with a sense of wry humanity:

Women selling snakeskins and alligator tails

Trying to get money to get my man out of jail

How much of that dog can I stand?

Said I was an angel, he was bound to treat me right

Who in the devil ever heard of angels that get beat up every night?

How much of that dog can I stand?

Gladys Bentley was born on Aug. 12, 1907, to Mary Bentley, who was from Trinidad, and George Bentley, an American, and she was raised in Philadelphia. (While most sources list Philadelphia as Bentley’s birthplace, during a rare TV appearance in 1958, she told Groucho Marx that she was originally from Port of Spain, Trinidad.)

The eldest of four siblings, Bentley remembered her childhood as an unhappy one, and from an early age her parents worried about her attraction to women. But she poured her frustrations and self interrogations into music, and her talents as a pianist and songwriter showed themselves quickly. In 1923, at 16, she left home for New York City, where the Harlem Renaissance was already in high gear.

Bentley immediately began performing at house parties and at so-called buffet flats. These were illicit clubs, usually in brownstones, that offered music, alcohol, gambling and often prostitution. But it was at the Clam House — Harlem’s most popular gay-friendly speakeasy, on 133rd Street, nicknamed Swing Street for its countless underground clubs — that Bentley established herself as the main attraction.

Her reputation took off. The house became the talk of Harlem, attracting uptown bigwigs as well as celebrities from all over the city. Bentley’s performances there inspired characters in at least three novels based on Harlem’s night life, including Carl Van Vechten’s voyeuristic “Parties.”

Source: nytimes.com