An article from NeglectedBooks.com

(First published 6 November 2011)

Brown Face, Big Master, is a book written by Joyce Gladwell who is mother to the famous and biggest non-fiction writer in the world, Malcom Gladwell. In it we get an insight into what life was like for his black mother, and how he was bought up.

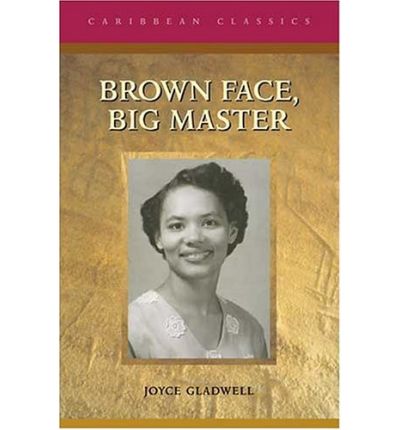

Cover of first UK paperback edition of ‘Brown Face, Big Master’

Cover of first UK paperback edition of ‘Brown Face, Big Master’

Knowing I would have the chance to hear Malcolm Gladwell speak at the PMI Global Congress last week, I stuck the fairly beat-up paperback copy of his mother Joyce’s 1969 memoir, Brown Face, Big Master, in my backpack and read it on the plane from Amsterdam to Dallas.

Aside from the family connection, Joyce Gladwell’s book has little in common with her son’s best-sellers. Although Brown Face, Big Masterhas been reissued by MacMillan Caribbean as part of its series of Caribbean Classics, it was first published by InterVarsity Press, the publishing arm of the InterVarsity Fellowship, and its focus is very much on tracing the development of the author’s faith and relationship with God, with a lesser theme of coming to grips with racism in its overt–and more often, subtly covert–forms.

The child of the principal and one of the teachers of a rural Jamaican school, Joyce Gladwell (nee Nation) grew up relatively isolated from the society around her. Her schoolmates were cautious not to get too friendly with Joyce or her twin sister, fearing that any secrets shared would find their way back to the school’s master. She and her sister were then sent to St. Hilary’s, a strict, though integrated, girls’ school, where the students were instructed to avoid speaking with the school’s staff and where private screenings were arranged in the local cinema to ensure no “inappropriate” contact with local boys.

St. Hilary’s had high standards, high moral standards, high standards of social behavior. We learned to believe in these standards, to accept them as the best, to live by them and to pass them on without compromise. I gave my unquetioning loyalty to St. Hilary’s. This was what I wanted–to belong, to be identified, to be approved, and St. Hilary’s filled that need.

Adding to school’s artificial isolation was Joyce’s own severe inhibitions. “I made myself comfortable in the security of being told exactly what to do and I was pleased to abdicate responsibility for my actions.” The cocoon was further extended when, shortly after graduation, she was asked to return as a teacher, and stayed for three more years, until she was offered a partial scholarship to London University.

Although she joined her twin sister, who had started at the university two years before, Joyce knew she was ill-prepared for the move from a sheltered girls’ school in Jamaica to a major university in the heart of one of the world’s great cities. “The world of people–that was where the trouble lay,” she writes. She proved an excellent student, and gradually, with the help of acquaintances in the school’s InterVarsity chapter, came out of her shell.

She fell in love with a fellow student, Graham Gladwell, a mathematician and InterVarsity member. Graham’s parents were initially resistant to the idea of their marrying, but eventually softened (“All marriages are mixed,” a family friend quipped). Still …

The moments of embarrassment that we feared did come. On one of our early visits to my parents-in-law, an old friend of the family called after long absence. We stood together with Graham’s sisters as Dad identified each one of his now grown family. “And Joyce, Graham’s wife,” he ended.

The visitor searched the faces round him in silence, seeking and failing to find the extra one that suited that description. We were paralysed by the dread realized, caught unprepared in an aberrant social moment for which the rules did not prescribe.

The couple went through some tough years, with Joyce struggling simultaneously with motherhood (she had had little preparation in domestic matters), long dreary grey English winters, and an ever-present undercurrent of prejudice. Finally, after a number of years and the birth of her third child–Malcolm–she had a breakthrough when she turned to God after a local boy shouted “Nigger” at her one afternoon. Ironically, she found her prayers answered not in understanding but in a challenge: “He showed Himself to be not only love giving Himself for me even to death, but also jealous God making demands on me”–demands to which she was now ready to yield.

Brown Face, Big Master is a restrained, subdued memoir, marked more than anything by a pervasive sense of humility. It is not at all an evangelical account: Joyce Gladwell’s own faith came to her gradually, over the course of many years, and with more than a few set-backs, and she makes no claims or and sets no expectations for others. In that respect, it is an account of one person’s faith that even non-believers can appreciate.