By Les Leopold and AlterNet

First Published: October 28, 2015

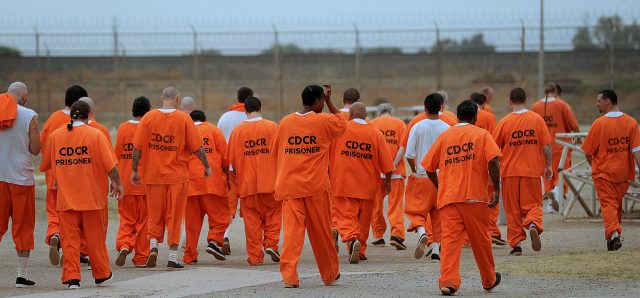

Our political and media elites should be ashamed of themselves. It’s taken nearly 20 years for them to realize that America is the largest police state in the world — that we have more prisoners than China or Russia both in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the population.

This Rip Van Winkle awakening is now leading to handwringing calls for the release of minor “offenders” and rethinking the arrest of people for selling cigarettes on street corners or “driving while black.”

Incredibly, the head of the FBI frets that a new crime wave may result from being too mindful about preventing overt, racist police brutality. But of course, he has no explanation for how the “home of the free” became a gulag.

That explanation will be hard to come by until elites admit that they destroyed any and all efforts to create public jobs and expand social programs for those struggling to survive. They incarcerated the War on Poverty.

If we listen carefully to today’s crop of politicians, we will find precious few (Bernie) who have the nerve to call for the creation of public jobs to bring down the 50% unemployment rate for black youths. Instead, they still sing from the old conservative hymnal about how “stimulating” the private sector will provide good jobs for all.

Sadly, that song is playing taps for America’s youth, especially those of color.

This excerpt from Runaway Inequality: An Activist’s Guide to Economic Justice provides further context and background.

America is number one in prisoners

By every measure the U.S. leads the world in prisoners, with 2.2 million people in jail and more than 4.8 million on parole. No nation tops that – not China with 1.7 million, not Russia with 670,000. The chart below shows the dramatic rise of the state and federal prisoner population as well as local jail inmates since the Better Business Climate model [the neo-liberal philosophy of cutting taxes, government programs and regulations] took hold.

Adult Persons in Jail or Prison

We not only have the highest number of prisoners, we have the highest percentage of people in prison or jail. In the U.S., 702 of every 100,000 people were in prison or jail in 2013. Cuba has 510 per 100,000 people in prison, Russia has 467, and Iran has 290.

Black and Latino Americans have been especially hard hit: they form over 39 percent of the prison population. One in every three black men is expected to serve time during their lives (at least under our current criminal justice system). Approximately half of all inmates are there for violating drug prohibition laws.

How is it that America, supposedly the beacon of freedom and democracy for the rest of the world, has more prisoners than any police state?

Did we suddenly become a crime-ridden country in 1980?

Those who study the question say that four factors explain the dramatic rise in U.S. incarceration: 1) overt racism; 2) Nixon’s ill-fated War on Drugs; 3) punitive laws like New York State Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s “three strikes” legislation; and 4) the 1984 Sentencing Reform Act, which forced judges to issue harsh minimum sentences.

But these explanations don’t tell the whole story. After all, racism was much more virulent earlier in American history. Until the civil rights movement, blacks were routinely denied their most basic civil rights. And yet the prison population was stable (and low, compared to now) through the 1940s, 1950s, and the turbulent 1960s.

Why are these Draconian laws so rigorously enforced? Why have we seen such a dramatic rise in criminal justice expenditures for police, courts and prisons? And why are so many people engaging in underground job activities that put them at risk of imprisonment? The four explanations above don’t answer these questions.

Deja vu all over again?

We have cast our eyes on many charts that suggest that something major happened around 1980. In fact, many of these charts have a similar shape: they all have a steeply rising hump on the right side, after 1980. We’ve already seen that all these things changed dramatically beginning around 1980:

• Wage increases no longer rise along with productivity.

• The CEO-worker wage gap takes off.

• Wall Street incomes shoot up while non-financial incomes stall.

• Wall Street profits skyrocket.

• The income gap between the super-rich and the rest of us widens rapidly.

• Taxes on the super-rich plunge.

• Corporate debt, consumer debt, student debt, and government debt all leap upward.

• The prison population explodes.

How do these trends fit together?

Unleashing Wall Street destroys manufacturing, older urban areas and America’s standard of living

As we know, at the end of the 1970s, conservative economists persuaded U.S. leaders to experiment with a new kind of shock therapy aimed at ending stagflation (the crushing combination of high unemployment and high inflation): We would simultaneously deregulate Wall Street, cut social services to the bone, and slash taxes on the wealthy. This, in theory, would spur new entrepreneurial activity that would eventually trickle down to the rest of us.

Entrepreneurial activity did increase (on Wall Street, anyway), but with disastrous results for middle- and low-income workers. Rather than create new jobs and industries that would promote shared prosperity, the newly invigorated Wall Street instead began to financially strip-mine American manufacturing. Their main goal never was to produce tangible goods and services, but rather to make more money from money.

Wall Street’s core American product is debt. Wall Street profits depend on loading up the country with it, and then collecting fees and compound interest on their loans.

Among the big debtors: state and local governments. And these are especially important to the incarceration story.

To review the story so far: After deregulation, waves of financial corporate raiders (now politely called managers of private equity firms and activist hedge funds) swooped in to suck the cash flow from healthy manufacturing facilities. They did this by buying up companies, loading them up with debt, and then cutting expenses to pay back the loans and enrich themselves.

Under this “downsize and distribute” policy, the raiders cut R&D, snatched pension funds, and slashed wages and benefits, decimating good-paying jobs in the U.S. and shipping many of them abroad. Nearly half of the raided companies failed, and in a few short years, America’s heartland turned into the Rust Belt. Better paying manufacturing jobs declined.

But Wall Street prospered like never before: Its profits rose to account for 43 percent of all domestic corporate profits by 2002 up from an average of about 12 percent from 1947 to 1980.

Impact of the Better Business Climate model on lower income Americans

The catastrophic collapse in manufacturing jobs was particularly tragic for African Americans. They had seen their standard of living rise during postwar years as they found higher paying, often unionized industrial jobs. But thanks to Wall Street raids, millions of these industrial jobs disappeared. There were still some jobs to be found in the service sector, but they paid about half of what manufacturing once paid.

The more fortunate Black and Latino men and women found work in the public sector, which was often unionized and paid a livable wage. But many more people had to take jobs in fast food chains, box stores, warehouses, and in the lower ranks of the health care system.

Overall, the Better Business Climate model brought soaring unemployment rates for young people, especially young people of color.

Many of the workers hit by these blows – people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds – found themselves in desperate straits, and some were forced to rely on the underground economy to survive.

The Ferguson scam: Using the courts to raise revenues from the poor for local government

It is a known fact that our judicial system discriminates against black and brown residents. The Sentencing Project reports that:

• Young, black and Latino males (especially if unemployed) are subject to particularly harsh sentencing compared to other offender populations; ·

• Black and Latino defendants are disadvantaged compared to whites with regard to legal-process related factors such as the “trial penalty,” sentence reductions for substantial assistance, criminal history, pretrial detention, and type of attorney;

• Black defendants convicted of harming white victims suffer harsher penalties than blacks who commit crimes against other blacks or white defendants who harm whites;

• Black and Latino defendants tend to be sentenced more severely than comparably situated white defendants for less serious crimes, especially drug and property crimes.

Similarly, the American Civil Liberties Union finds that “Black people are 3.7 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than white people despite comparable usage rates.”

Why are people of color targets for increased arrests and incarceration? Normally the explanation is simply racism. But the Justice Department report on the events in Ferguson, Missouri show the invisible hand of the Better Business Climate model hard at work.

As stagnant wages and tax cuts for the rich squeeze state and local governments for funds, those jurisdictions look for new ways to raise money. One answer is to squeeze the poor through increasing the number of arrests and fines. Why? Because the poor have fewer resources with which to fight back. As the Justice Department report puts it:

“Ferguson has allowed its focus on revenue generation to fundamentally compromise the role of Ferguson’s municipal court. The municipal court does not act as a neutral arbiter of the law or a check on unlawful police conduct. Instead, the court primarily uses its judicial authority as the means to compel the payment of fines and fees that advance the City’s financial interests. This has led to court practices that violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process and equal protection requirements. The court’s practices also impose unnecessary harm, overwhelmingly on African-American individuals, and run counter to public safety.”

Amazingly, Ferguson amped up its revenue collection after the Wall Street crash decimated the economy as Chart 9.2 clearly shows.

Percent of Ferguson, MO Revenues from Fines and Forfeitures

And it’s not just Ferguson. We know for certain that the rest of St. Louis county is playing the same game. As the Washington Post reports:

“Some of the towns in St. Louis County can derive 40 percent or more of their annual revenue from the petty fines and fees collected by their municipal courts. A majority of these fines are for traffic offenses, but they can also include fines for fare-hopping on MetroLink (St. Louis’s light rail system), loud music and other noise ordinance violations, zoning violations for uncut grass or unkempt property, violations of occupancy permit restrictions, trespassing, wearing “saggy pants,” business license violations and vague infractions such as “disturbing the peace” or “affray” that give police officers a great deal of discretion to look for other violations. In a white paper released last month, the ArchCity Defenders found a large group of people outside the courthouse in Bel-Ridge who had been fined for not subscribing to the town’s only approved garbage collection service. They hadn’t been fined for having trash on their property, only for not paying for the only legal method the town had designated for disposing of trash.”

We also know that Missouri’s Attorney General in 2014 sued 13 municipalities for relying too heavily on traffic fines to fund local government. Four of the municipalities received 30 percent or more of revenues from traffic fines and the rest did not provide the legally-required information to determine the percentage.

The extent of this discriminatory revenue-raising across the country is currently unknown. But it is certain to extend far beyond the wide Missouri.

Financialization and gentrification

Financial strip-mining not only destroys middle-income manufacturing jobs, it destroys affordable housing by encouraging gentrification.

The rise of high-income financiers (along with banks eager to loan to them) creates upward pressure on housing prices in cities that cater to elites like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Real estate development is lucrative in areas where land values are rising rapidly.

Inevitably, lower-income residents are squeezed out, and their homes are turned into fashionable townhouses, coops, and condos for the wealthy. (Typically, the young adult children of the well-to-do unconsciously serve as the forward troops for gentrification as they flock into the cheaper neighborhoods of big cities.)

Gentrification and the “Broken Windows” theory of crime prevention

The commingling of the affluent and those living on the margins of the underground economy in gentrifying neighborhoods is explosive. Higher-income residents call for more protection and a halt to “crime in the streets.”

Urban police departments, led by New York, began adopting the “Broken Windows” theory of crime prevention in the 1980s. The idea was that by targeting minor infractions (like drinking on the street, loitering, pan-handling, or selling loose cigarettes), police can prevent a slide to bigger crimes. The metaphor is that a neighborhood with no broken windows gives the community and its residents a more positive image, making it safer and less conducive to crime. It’s a highly debatable theory. But it has unquestionably led to more arrests.

Inevitably, the combination of gentrification on one side, and joblessness and poverty on the other leads to more police patrols and arrests – including “stop and frisk” programs that disproportionately target people of color. The prison population surges.

In short, financial interests working to transform poorer neighborhoods into desirable real estate for the newly minted elites have an interest in ridding the neighborhood of the troublesome poor. Jail becomes the new home for many.

Downward pressure on the pubic sector

The housing bubble and bust hit low-income neighborhoods hard. Regions that were already struggling, including the Rust Belt, were decimated by the Wall Street crash. Joblessness spiked (again) and business and worker tax revenues fell. This led to more cuts in the public employee jobs that so many displaced manufacturing workers had relied on. Public sector services also got chopped.

Detroit became the poster child for ravaged American cities everywhere: First corporate raiders and private equity firms squeezed the life out of manufacturing all over Michigan. Then the Wall Street crash destroyed more jobs and undermined the tax base. And that led to urban bankruptcy and even more public sector job loss.

The Better Business Climate model’s dirty little secret: Jail is America’s jobs program

What will happen to all our unemployed people, given the massive shortage of jobs?

What will happen to people trapped in neighborhoods crammed with foreclosed homes?

Where are the job programs for the millions who need them?

In theory, the Better Business Climate model was going to lead to a boom that would create jobs for all those willing and able to work.

In practice, financial strip-mining did just the opposite. It caused decent jobs to evaporate, forcing cash-strapped cities to lay off public employees. Policing costs rose, squeezing the budget for social services and education. You had to be blind not to notice that those on the bottom were in serious trouble.

To cover for this abject failure of the Better Business Climate model, its supporters developed a novel jobs program that is now de-facto government policy: Put the dislocated, the unemployed, the “surplus” youth in jail.

If incarcerating the poor turned America into the biggest police state in the world (and it did), so be it.

This is a remarkable shift in America’s approach to joblessness. From the New Deal to the 1980s, the government had a strategy for dealing with enormous structural unemployment and poverty: it created jobs. Now, it puts the jobless in prison.

The Prison-industrial complex

The rapidly expanding prison sector warehouses millions of low-income people. But it also creates new jobs and profit opportunities.

As we know, the Better Business Climate model calls for privatizing public services. The idea is that privatizing generates new businesses and profits and it reduces the size of government. Plus, supporters claim that privately run businesses are always more efficient than the government.

Clearly, the growing prison population creates enormous privatization profit opportunities.

The first private prison opened in Tennessee in 1984. As of 2013, U.S. Department of Justice statistics show that there were 133,000 state and federal prisoners housed in privately owned prisons in the U.S., constituting 8.4 percent of the overall U.S. prison population.

Correctional, police, and judicial jobs at all levels of government have also grown dramatically since the early ’80s, nearly doubling from 1.3 million in 1982 to 2.4 million in 2012.

The prison guard unions and the private prison corporations (along with their Wall Street backers) have a vested interest in expanding the private prison system. Unfortunately for poor people, this requires rounding up more prisoners.

Incarceration’s color coding

The prison statistics describe an America stratified by skin color, as Chart 9.3 makes painfully clear. How do we account for that?

In this chapter we provide part of the answer: the financial strip-mining of our economy had an extremely negative impact on older urban areas where many people of color live. It also reduced the number of manufacturing jobs and then public employee jobs that minorities rely upon to move up the income ladder. In addition, statistics show that people of color are more often targeted for arrest, arrested for more minor crimes, and given longer sentences.

But lurking in the background is perhaps the most difficult question that America faces, and that we turn to in the next chapter: After all these years, why are people of color still overrepresented at the bottom of the income ladder?