by Jamie Doward

First published Sun 12 Jan 2014

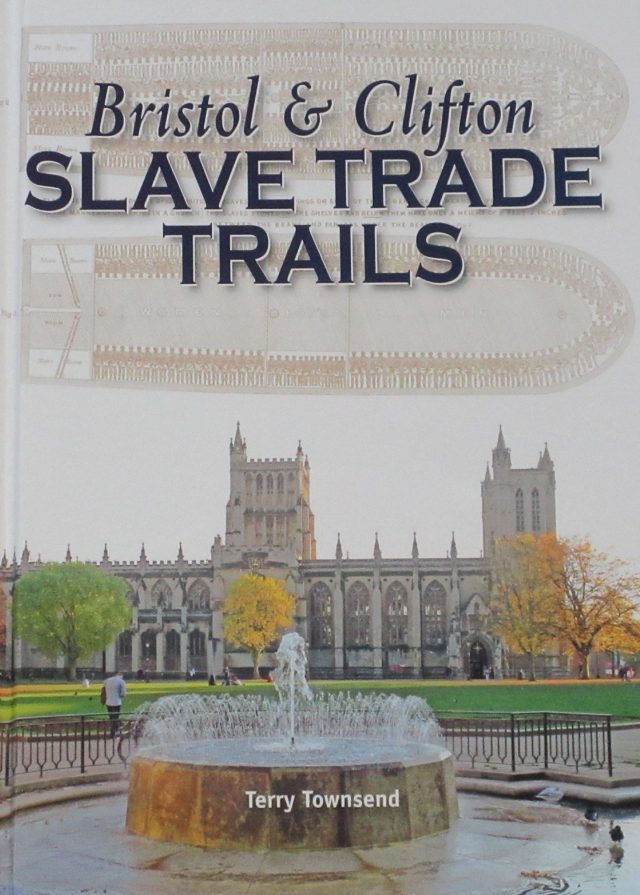

As the film, ’12 Years a Slave’ reminded cinema-goers of the terrible trade, a walk through Bristol reveals how the splendid Georgian townhouses were financed by the suffering of west Africans.

Ani DiFranco, an American folksinger, feminist and social justice campaigner, in 2013 found herself forced to withdraw from a songwriting festival in Louisiana. DiFranco’s “righteous retreat”, she discovered only after signing up for the event, was to be held in a luxury resort whose owners have been criticised for airbrushing out of history the fact that it was once the largest slave plantation in the American south.

In an apologetic posting on her website, DiFranco wrote: “One cannot draw a line around the Nottoway Plantation and say ‘racism reached its depths of wrongness here’ and then point to the other side of that line and say ‘but not here’,” DiFranco said. “I know that any building built before 1860 in the south, and many after, were built on the backs of slaves.”

Indeed, as the acclaimed film, 12 Years a Slave, is brutally reminding cinema audiences, the US economy was built on the back of forced labour. The fact that it was a British-born director, Steve McQueen, who made the film, which tells the story of Solomon Northup, a free man kidnapped into slavery, is a cause for celebration but also surprise for some British historians.

“I would be fascinated to know why as a black British director he didn’t pick a black British experience,” said Dr Kate Donington, research associate at UCL’s Legacies of British Slave-Ownership Project, an online archive that allows users to identify those who benefited from slavery.

Donington believes a film examining Britain’s role would be a healthy corrective to the “tendency to see slavery as something that happened in America”. One reason for this myopia is Britain’s leading role in outlawing the slave trade. The 2007 bicentenary of its abolition largely became a celebration of Britain’s achievements, rather than a chance to face up to unpalatable home truths. “You can’t tell the story of Britain’s role in abolishing slavery without first engaging with its long history of participation in the slavery business,” Donington said.

Indeed, as the UCL project makes uncomfortably clear, the creation of modern Britain owes much to slavery. A walk through a cold, grey Bristol on Friday made this argument in physical terms. Guinea Street, a stern terrace of five-storey houses on the dockside, was home to the slave traders and owners Edmund Saunders and Joseph Holbrook. Guinea was the name give n to western Africa by those who sought their fortunes in slavery. The Guinea coin was produced by Bristol’s Royal African Company (RAC), whose members became arch-practitioners of the trade.

Nearby is Queen Square, a collection of attractive Georgian houses that were home to many of the wealthiest slave traders. The Sugar House, now a hotel, in Lewin’s Mead, was one of many refineries that processed sugar harvested by slaves in the Caribbean.

Then there is Colston Hall, a major music venue named after Edward Colston, a philanthropist and merchant who paid for several schools, churches and hospitals, many of which survive to this day. Much of Colston’s wealth came from the trade – and his investments in the RAC. The Bristol band Massive Attack have pledged never to play at the venue until its name is changed.

On Corn Street is an impressive, honey-coloured building with a worn stone pl aque proclaiming “the Old Bank”. The bank was formed by slave traders and, after being merged with others, went on to become the NatWest.

Such buildings are testimony to a trade that was conducted with extraordinary vigour. It is estimated that Britain transported more than three million African people across the Atlantic (500,000 on Bristol ships alone), an epic trade that involved some 10,000 voyages and swelled the coffers of the owners. By the Victorian era, as many as one in six of the wealthiest Britons derived at least some of their fortunes from slavery. Few seemed to have any qualms. The Quakers, for example, had been enthusiastic investors.

“Before 1760, they were up to their eyeballs in it,” said Madge Dresser, associate professor in history at the University of the West of England. Later they were in the vanguard of the 19th-century antislavery movement.

And after abolition finally came, those who had participated – including, as the UCL project reveals, the ancestors of Graham Greene, George Orwell and Elizabeth Barrett Browning – were handsomely compensated for their lost income.

In 1833 parliament approved the payment of £20m to the former slave owners – 40% of the government’s expenditure that year, equivalent to £16bn in today’s money. Much of the wealth generated was concentrated in the West Country.

“When I looked at the merchants in Bristol behind the Georgian flowering of architecture, the so-called urban renaissance, they virtually all had either slave-trading connections or connections with slave-produced foods or government connections with plantation interests,” said Dresser, co-editor of a new book, Slavery and the British Country House.

Other cities, notably London, Liverpool and Glasgow, benefited significantly too, and even the most rural parts were not untouched. Many of the country’s finest stately homes were built partly out of the proceeds of slavery. Dresser’s book refers to more than 150 British properties, many run by the National Trust and English Heritage, that have links to slavery. And yet, unlike in the US, few in Britain appreciate how their country’s history has been shaped by the slave trade. “The issue of geographical distance is fundamental to understanding why the experience of slavery is not as well known in Britain,” Donington said. “Most of the people were on the plantations in the Caribbean so there are not what Toni Morrison describes as ‘sites of memory’ that you can hang [British] history on. It becomes a process of palimpsest – you have to uncover layer after layer of history in country houses and, in places like Bristol, its big Georgian townhouses.”

One such Bristol townhouse, number 7 Great George Street, now a museum, was once the handsome home of John Pinney, a plantation owner in the Caribbean, whence he brought back a slave, Pero Jones, after whom a dockside bridge is named.

Jones’s story is not unique. There were 15,000 black people in Georgian Britain, most living in London. Some had earned their freedom, having served in the Royal Navy. Most were classed as servants. But their status was a legal grey area that left the position of Africans in Britain unclear.

One of the best documented accounts by a black person of the time, which has uncanny parallels with that of 12 Years a Slave, was provided by Olaudah Equiano who, according to his autobiography, was born in what is now southern Nigeria (this is disputed) before being captured and taken to Barbados and then Virginia before being sold on. Equiano ended up the property of a British naval officer. Having risen to the rank of able seaman, he was freed, only to be re-enslaved in London in 1762 and shipped to the West Indies, where he accumulated enough money to buy his freedom and return to England, where he married and became a prominent abolitionist.

Source: Guardian.com