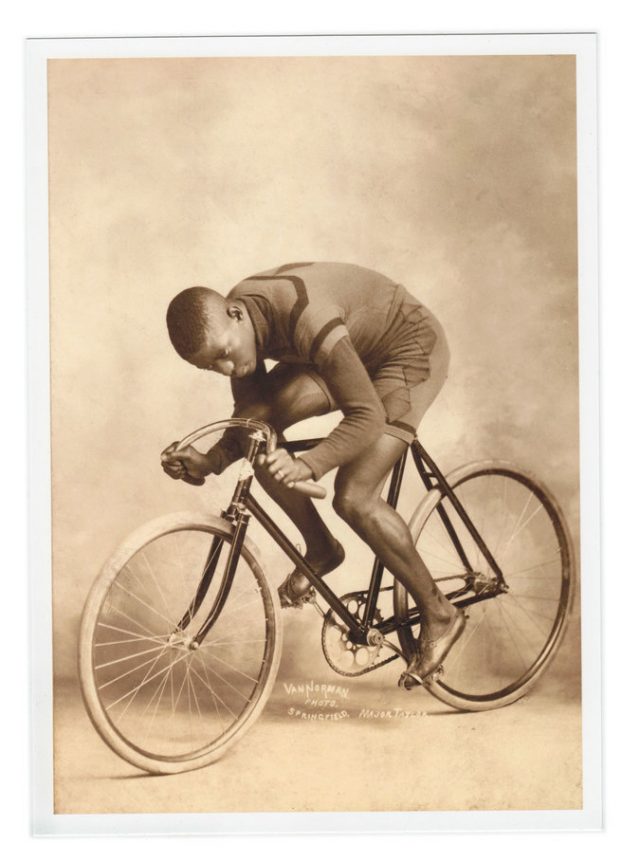

Major Taylor

A world champion bicycle racer whose

fame was undermined by prejudice.

BY Randal.C Archibold

More than 100 years ago, one of the most popular spectator sports in the world was bicycle racing, and one of the most popular racers was a squat, strapping man with bulging thighs named Major Taylor.

He set records in his teens and was a world champion at 20. He traveled the globe, racing as far away as Australia, and amassed wealth among the greatest of any athlete of his time. Thousands of people flocked to see him; newspapers fawned over him.

Major Taylor was the “Black Cyclone,” at once the LeBron James and Jackie Robinson of his time. He blew past racial barriers in an overwhelmingly white field bent on stopping him, sometimes violently.

He was the first African-American world champion in cycling and the second black athlete to win a world championship in any sport.

So consider this: He died penniless in 1932, at age 53, and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

The head-spinning arc of Taylor’s life is a story too little told.

He endured racial hostility — including a brutal beating at a race and more than one episode of sabotage on the course — yet he persevered and professed to bear no animosity.

“Life is too short for a man to hold bitterness in his heart,” he wrote in his self-published 1928 autobiography, “The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds.”

He lived a life of triumph and tragedy seemingly made for Hollywood, yet by the end of his life could barely sell copies of his book.

“To imagine what he went through in the 1890s is unimaginable,” Edwin Moses, an Olympic gold medalist in track and the honorary chairman of the Major Taylor Association, said in a telephone interview. “I could not imagine competing and being a winner with what he put up with.”

Major Taylor was not actually a major.

Marshall Walter Taylor was born in Indianapolis on Nov. 26, 1878, one of eight children of Gilbert and Saphronia (Kelter) Taylor. He acquired his nickname as a boy doing bicycle tricks outside a cycle shop while dressed in a military uniform to attract customers.

The shop’s owner, Tom Hay, entered Taylor in his first race, a 10-miler, and he won by six seconds. He was 13.

But despite his victories and his jaw-dropping times, Taylor was not allowed to join cycling clubs in Indiana and was barred from tracks. So a savvy racing manager and bicycle manufacturer named Louis Munger, known as Birdie, persuaded him to move to Worcester, Mass.

“I was in Worcester only a very short time before I realized that there was no such race prejudice existing among the bicycle riders there as I had experienced in Indianapolis,” Taylor wrote in his autobiography.

In 1896, Munger entered Taylor in a grueling six-day race at Madison Square Garden (a television commercial for Hennessy cognac, released last year, celebrates his performance in that race). It crushed him physically but catapulted him, just after his 18th birthday, into the world of professional cycling.

“He had to be terrified,” said Karen Brown-Donovan, his great-granddaughter, in an email, adding, “especially since he was the only person of color on the track.”

“The fact that he lasted for the duration of the six-day race was astonishing,” she said.

In 1899, he shocked the world by winning the one-mile sprint at the world championship in track cycling, the second black athlete, after the Canadian bantamweight boxer George Dixon, to win a world title in a recognized sport.

But for all his newfound celebrity, racism still held him back, even in Worcester.

When he moved into a new house, his neighbors at first tried to get him to relocate.

And with Jim Crow laws in full force, he wasn’t spared on the track, either.

Ice water was thrown at him and nails laid in the path of his bicycle by members of rival racing teams. Riders routinely jostled and elbowed him — and he still won.

Perhaps the worst incident, covered in The New York Times, was in September 1897. After a one-mile race in which Taylor placed second, the third-place finisher, William Becker, “wheeled up behind Taylor and grabbed him by the shoulder. The colored man was thrown to the ground, Becker choked him into a state of insensibility, and the police were obliged to interfere.”

Becker accused Taylor of crowding him, something nobody else saw. He was later fined $50 but was allowed to continue racing.

The hotbed of cycling was Europe, but it took some time before Taylor would compete there. Many of the races were on Sundays, and Taylor, a devout Baptist since his mother’s death in 1898, refused to race then — a conviction that inspired the Otis Taylor blues song “He Never Raced on Sunday.”

Still, Taylor had become so famous that race organizers eventually moved events to weekdays to accommodate him. He was embraced in France and beat every European champion, further sealing his iconic status.

“Major Taylor had a proud and confident identity in Europe and was not a crushed or threatened black man,” Andrew Ritchie wrote in his 1988 biography, “Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer.”

As The Times marveled during a 1903 tour in Australia, “he has won many big prizes and is making money at a rapid rate.”

Eventually, age and younger competitors caught up with Taylor. He retired in 1910, then struggled to capitalize on his success. Interest in cycling was fading as the automobile captivated the public. He made bad investments — including the self-published autobiography — and his savings were further devastated by the 1929 stock market crash, all but erasing his fortune. His health declined and his marriage, to Daisy Victoria Morris in 1902, fell apart.

“Once he was done as a sports person his opportunities dried up,” said Todd Balf, author of “Major: A Black Athlete, a White Era, and the Fight to Be the World’s Fastest Human Being,” published in 2008. “I can only imagine the stress and strain of trying to make a go of it.”

He moved to Chicago, rented a room at a YMCA and tried going door-to-door to sell the book, “but there was no second chance after he retired from racing,” Ritchie said.

He died on June 21, 1932, alone and largely forgotten, his body unclaimed in the morgue. There was a short obituary in the African-American newspaper The Chicago Defender.

“This was a tragic event for someone who had received so much acclaim during his lifetime,” said Brown-Donovan, his great-granddaughter. Her grandmother Sydney Taylor Brown (named for the city she was born in) was his only child.

“My grandmother always hated that he died this way,” she said. “She didn’t know he was so ill.”

Before he left for Chicago, Taylor gave his daughter “every tangible memory of his cycling career — his journals, scrapbooks, photos, trophies, medals, letters, etc.,” Brown-Donovan continued. “This is why my grandmother became a fierce protector of his legacy for the rest of her own life. People know about Major Taylor today because of Sydney Taylor Brown.”

Cycling today remains a predominantly white sport, though a number of athletes have come to know and be inspired by Taylor’s story and several cycling clubs have adopted his name.

Still, “at the pro level, there has never been anybody who walked in his shoes,” Balf said.

Taylor’s body was in a pauper’s grave for years in Mount Glenwood Memory Gardens, near Chicago. In 1948, a group of former racing stars had him reburied, with financial assistance from Frank Schwinn of the Schwinn Bicycle Company, in the cemetery’s Garden of the Good Shepherd. There is now a memorial outside the Worcester Public Library as well.

The plaque on his grave reads:

World’s champion bicycle racer who

came up the hard way without hatred in his heart,

an honest, courageous, and God-fearing, clean living gentlemanly athlete,

A credit to his race who always gave out his best. Gone but not forgotten

Source: nytimes.com