by Dean Smart

The port of Bristol

From the late 1300s to the mid-18th Century, Bristol’s main income was related to seaborne trade, and the need for profit was a strong motivating force. Consequently Bristol ship owners were always looking for lucrative new routes and new business opportunities; some merchants are recorded as having sent children as slaves to Ireland as early as the 12th Century.

By the 18th Century Bristol was England’s second city and port, and as a result of this prosperity a building and investment boom took place in Bristol and nearby Bath. Local merchants voraciously lobbied King William III to be allowed to participate in the African trade, which until 1698 was a crown monopoly granted to The Royal African Company.

Bristol merchants were granted the right to trade in slaves in 1698 and it did not take them long to turn the business opportunity into profit. From 1698, to the end of the Slave Trade in Britain in 1807, just over 2,100 Bristol ships set sail on slaving voyages. According to Richardson (The Bristol Slave Traders: A Collective Portrait Bristol: Historical Association, Bristol Branch, 1984) this amounted to around 500,000 Africans who were carried into slavery, representing just under one fifth of the British trade in slaves of this period.

During this time an average of 20 slaving voyages set sail from Bristol each year, with many of the earliest voyages based on multiple investors, sometimes with “ordinary” people providing a quantity of cash or trade goods to be bartered for captured Africans at the end of the outward passage. Later voyages seem to have relied on one or two wealthy investors, perhaps with an eye to not diluting the profits! Clearly many Bristolians were happy to be involved in slavery if it meant getting rich.

Preparing a ship for a slaving voyage, as opposed to a non-slave trading mission, was no simple feat since it required much higher investment to fit out, provision and crew. For example the hull required special plating to prevent the Toredo Worm, a wood boring worm, whose natural habitat is in warmers waters, from breaching the hull in the two to nine months that it took to buy and load slaves off the coast of Africa, and further time to offload and sell slaves, clean the ship, and reload with other goods in the Americas or West Indies.

However investing in a slaver did not guarantee profit. Mortality was high onboard ship and there was an expectation that perhaps a tenth of the “cargo” and crew might die before reaching the colonies.

Bristol’s involvement in the slave trade peaked between 1730 and 1745, with the city becoming the leading slaving port, and tremendous wealth came back to Bristol.

Africa bust, Corn Exchange

References to the Slave Trade are still visible in Bristol’s buildings.

© Dean Smart

But not all voyages were profitable, according to Madge Dresser, writer of Slavery Obscured: The Social History of the Slave Trade in a Provincial Port, as many as third of all voyages failed to yield the high profits the financiers wanted. This made the selection of a good ship’s master essential. The Ship’s Captain had to carefully stock and crew his ship, get it safely to Africa and then skilfully barter with African and Arab slave traders to obtain a good ‘cargo’ to carry to the West Indies.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade had a rapid and devastating impact on Africa. Unlike slavery in some traditional African societies, where slaves were often prisoners of war who might be held for some years and then released, or those born into slavery who were treated reasonably well, the “new” depopulation had a significant impact.

Tribes fought with tribes to acquire people to sell into slavery; this encouraged inter-tribal warfare and rivalry, bred a climate of distrust and fear, and removed some of the fittest and most able members of the community. The old, the very young, the infirm and the unfit were left or killed, and only those who might survive a walk of perhaps hundreds of miles to the coast, and still be attractive to buyers, were taken.

Today historians acknowledge that the Transatlantic slave trade slowed and changed the development of the African economy, as well as providing much of the venture capital for the industrial revolutions of Britain, Europe and the American colonies. Heated discussions continue about whether the Western and American governments should issue a public apology for the slave trade, and offer to pay reparations to the African and Caribbean nations for what some consider to be the equivalent of a war crime.

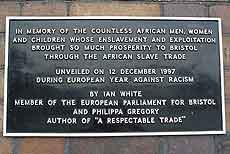

The Slave Trade brought wealth to many Bristolians.

The trade resulted in the forced removal of millions of captured Africans from Western and Central Africa to the West coast and from there to European colonies in North and South America and the West Indies. Although only a very few Africans ended up in Bristol while the trade was active, mostly as personal servants, or workers on board ships, this mass movement of people had a huge effect on the city of Bristol – its trade, its people, its development, and most of all its wealth.

In Bristol the principal financial gains from slave voyages and slave labour were made by the merchant classes. Trade and local politics was dominated by members of The Society of Merchant Venturers, a group which still exists today. Their power in the city in the past cannot be underestimated, and during the years of the slave trade 16 owners of ships which were slaver traders served as Masters of the Society, 16 served as Sheriff of Bristol, 10 as Aldermen and 11 as Mayor. Involvement in the trade was common amongst many of the City’s leading families.

Other members of the same families, or their relatives and friends, became plantation owners in the West Indies, and Bristol families like the Pinneys became fantastically rich by the standards of the time. With a vested interest in maintaining their profits from slavery these same families then fought to keep the slave trade when campaigns for its restriction and abolition were started in the late 18th Century.

Source: bbc.co.uk