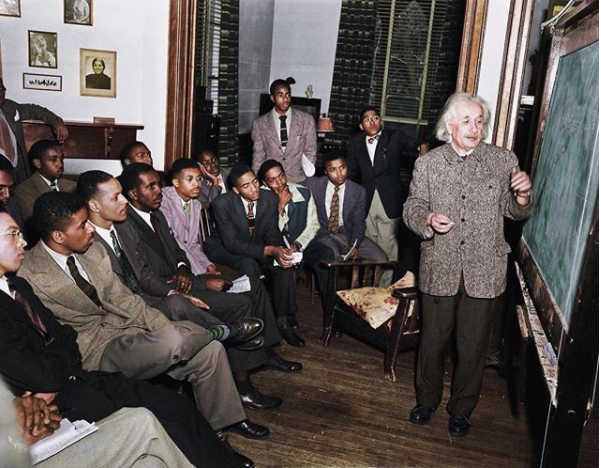

Former Vice President Henry Wallace, Albert Einstein, Lewis L. Wallace of Princeton University and Paul Robeson meeting in Princeton in 1947. Einstein and Robeson worked together to advocate racial justice for African Americans.

By Bill Sanservino

(Community News – January 26, 2015)

While groups like Not In Our Town Princeton are working today to create a dialogue about racial injustice in Princeton, almost 70 years ago was doing the same.

Although Einstein is best known for his theories that transformed the study of physics, most people don’t realize that he was an outspoken civil rights advocate, and it was racism and segregation in Princeton, in part, that eventually inspired the scientist to speak out against racism.

Einstein, who was all too familiar with the persecution of Jews in his native Nazi Germany, saw an analogous situation in the United States in the treatment of blacks and even found this to be the case in Princeton.

“Access to housing, jobs and the university itself were routinely denied to African Americans [in Princeton]; protest or defiance were often met with police violence,” wrote John J. Simon in an article in the May 1985 issue of the Monthly Review.

“Einstein, who had witnessed similar scenes in Germany, and who, in any event was a longtime anti-racism militant, reacted against every outrage,” Simon said. “In 1937, when the contralto Marion Anderson gave a critically acclaimed concert in Princeton but was denied lodging at the segregated Nassau Inn, Einstein, who had attended the performance, instantly invited her to stay at his house. She did so, and continued to be his guest whenever she sang in New Jersey, even after the hotel was integrated.”

In 1935, Einstein met Paul Robeson — a famous African-American singer, actor, and civil rights activist who grew up in Princeton — after a performance at McCarter Theatre. The two would eventually become friends and work together on civil rights causes. The two had something in common: Robeson’s feelings about growing up in Princeton were similar in many respects to the way Einstein viewed his boyhood in Nazi Germany.

Einstein had escaped from Nazi anti-Semitism, while Robeson described the Princeton he left behind as “a Georgia plantation town,” and “spiritually located in Dixie.”

“Almost every Negro in Princeton lived off the college and accepted the status that went with it. We lived for all intents and purposes on a Southern plantation. And with no more dignity than that suggests — all the bowing and scraping to the drunken rich, all the vile names, all the Uncle Tomming to earn enough to lead miserable lives,” said Robeson in a 1949 speech.

In 1946 Einstein became what we today might call a civil rights activist. It was in that year that he expressed a strong view against racism in article titled, “The Negro Question,” in the January issue of Pageant magazine.

“As one who has lived among you in America only a little more than 10 years… I am writing seriously and warningly,” Einstein said in the article.

“In the United States everyone feels assured of his worth as an individual. No one humbles himself before another person or class,” wrote the physicist. “There is, however, a somber point in the social outlook of Americans. Their sense of equality and human dignity is mainly limited to men of white skins.

“Even among these there are prejudices of which I as a Jew am clearly conscious; but they are unimportant in comparison with the attitude of the ‘whites’ toward their fellow-citizens of darker complexion, particularly toward Negroes. The more I feel an American, the more this situation pains me. I can escape the feeling of complicity in it only by speaking out.”

Einstein wrote that a person who believes that African Americans are not equal to whites in intelligence, sense of responsibility or reliability, “suffers from a fatal misconception.”

“Your ancestors dragged these black people from their homes by force; and in the white man’s quest for wealth and an easy life they have been ruthlessly suppressed and exploited, degraded into slavery,” he said. “The modern prejudice against Negroes is the result of the desire to maintain this unworthy condition.

“The ancient Greeks also had slaves. They were not Negroes but white men who had been taken captive in war. There could be no talk of racial differences. And yet Aristotle, one of the great Greek philosophers, declared slaves inferior beings who were justly subdued and deprived of their liberty. It is clear that he was enmeshed in a traditional prejudice from which, despite his extraordinary intellect, he could not free himself.”

Later in the article, Einstein said, “I believe that whoever tries to think things through honestly will soon recognize how unworthy and even fatal is the traditional bias against Negroes.

“What, however, can the man of good will do to combat this deeply rooted prejudice? He must have the courage to set an example by word and deed, and must watch lest his children become influenced by this racial bias.

“I do not believe there is a way in which this deeply entrenched evil can be quickly healed. But until this goal is reached there is no greater satisfaction for a just and well-meaning person than the knowledge that he has devoted his best energies to the service of the good cause.”

The article in Pageant wasn’t the first time Einstein had spoken publicly about the rights of African Americans. That came in 1940 during a speech at the Worlds Fair in New York.

“As for the Negroes, the country has still a heavy debt to discharge for all the troubles and disabilities it has laid on the Negro’s shoulders, for all that his fellow-citizens have done and to some extent still are doing to him,” he said.

A few months after the article was published in Pageant, Einstein made another public appearance to promote civil rights, this time at Lincoln University, the nation’s first degree-granting traditionally African American university.

In the 20 years before his death, Einstein rarely accepted invitations to speak at outside universities due to failing health and the fact that he found the degree presentations to be “ostentatious.” In May 1946, he broke his self-imposed rule to give an address and accept an honorary degree from Lincoln.

“My trip to this institution was in behalf of a worthwhile cause,” said Einstein in his address at Lincoln. “There is a separation of colored people from white people in the United States. That separation is not a disease of colored people. It is a disease of white people. I do not intend to be quiet about it.”

Einstein’s choice of Lincoln, as well as his words, were intended to send a message to a wider audience, said Fred Jerome and Roger Taylor in their 2006 book, Einstein on Race and Racism.

“But the media then — like the media now — had different news priorities,” they said. “While almost all of Einstein’s public speeches and interviews were extensively reported by major newspapers — even sticking out his tongue at a reporter made the front pages — the mainstream media treated the address by the world’s most famous scientist at the nation’s oldest black university as a nonevent. Only the black press gave Einstein’s speech meaningful coverage.”

At home in Princeton, Einstein dealt with racism and segregation in town by building relationships with the town’s African-American community — walking through their streets, stopping to chat with the inhabitants and handing out candy to local children.

“Nowhere in all the ocean of published Einsteiniana — anthologies, bibliographies, biographies, summaries, articles, videotapes, calendars, posters and postcards— will one find even an islet of information about Einstein’s visits and ties to the people in Princeton’s African American community around the street called Witherspoon,” said Jerome and Taylor.

“Somewhat to his embarrassment, Einstein became in the United States, as he had been in most of Europe outside Nazi Germany, a living metaphor for genius, ‘the smartest man on the planet,‘“said Jerome and Taylor. “He was the science superstar and the most famous man in Princeton. Yet Einstein only had to walk a few blocks down Witherspoon Street to be reminded of how fleeting freedom could be.”

In Einstein on Race and Racism, African American Princeton resident Lloyd Banks spoke about his experiences with Einstein as a youth.

“Einstein was unusual for a white person to a degree — he wasn’t bothered being in the black community. We would run out — as children we always ran out and talked to him and he would stop and talk to us. We would be shouting, ‘Dr. Einstein, Dr. Einstein,’ and he would stop and take a few minutes with us. He took the time to talk to us. He was very friendly.”

Days before he died on April 18, 1955, Einstein signed what became known as The Einstein-Russell Manifesto. In it, he and the philosopher-mathematician Bertrand Russell make an appeal for people to work together despite their differences.

“There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge, and wisdom,” the two said.

“Shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels? We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.”