By Mireille Gangenois

First published 30 June 2020

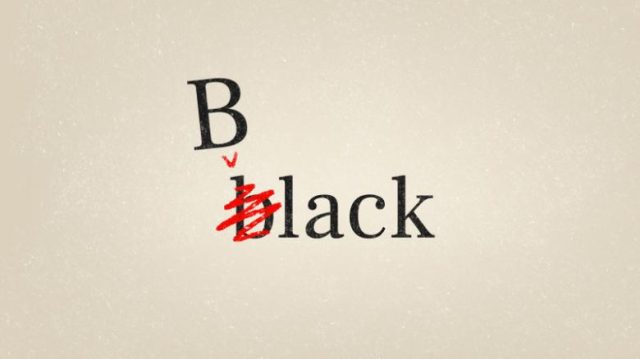

(CNN)The first letter to the editor I ever wrote was to David Lawrence Jr. at the Detroit Free Press — an early champion of diversity who went on to lead the Miami Herald and advocate for the rights of children. I implored him to change newsroom style and capitalize the “b” in the word “Black” when referring to African Americans. The year was 1981.

This month, spurred in part by protests against racial injustice convulsing the nation, newsrooms across the country have been debating this decades-old topic — and with some fanfare, some major ones have come down in favor of the capital B, including NBC News, CNN and The Associated Press.

Today, my perspective has changed. I’d say the “b” word debate is a red herring and I’d argue differently. (It feels strange to me to know that my lower case “b” will be converted to upper case here, even in a commentary where I suggest that perhaps they shouldn’t be.)Based on long experience in both editorial and corporate roles at a variety of news outlets, I contend more than a few top editors are likely quite relieved so many news consumers, media watchers and influencers are caught up in this style-guide sideshow — instead of focusing on the main event: transforming how journalism outlets address race and, in the process, leading a genuine transformation in how America confronts racism.

If newsroom leaders don’t acknowledge their own place on the spectrum of institutions the current protests are aimed at upending, they’re missing the story.

To those editors interested in a serious demonstration of how to respond to this unprecedented moment in America’s tragic racial condition, answer this: What percentage of editors in your newsroom are African American, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American or LGBTQ? Same question about your top tier of newsroom management? Apply the question for your bureaus — from city hall to the state house to the far reaches of the globe?

When those in your leadership took up the issue of whether to capitalize that “b,” did anyone press to confront these questions — and be transparent with your employees or audience about the answers?

Unless we can do that, the distraction prompted by the “b” word debate risks trivializing or sidelining the overdue conversations about race and racism, making them about case sensitivity and needlessly alienating potential allies who might otherwise be sympathetic.Before you grapple with the “b” word conundrum, answer this too: how does your editorial strategy address the evolving demographics of your local community or our nation as it becomes increasingly brown and younger than your legacy audience? Same question goes to your audience growth strategy.Why am I raising these questions? Because they speak to our society’s need for the best possible coverage — smart, consistent, accurate and courageous reporting — that brings an unflinching context and a deep meaning to this, one of the most difficult of issues in our democracy.

Not only does merely capitalizing the “b” not improve coverage to that standard, it may offer an easy cosmetic out to news organizations and indeed a wide set of corporations and institutions to assuage their need to feel like they’re on the right side of history.For well-meaning executives, to do or say something — anything –in this moment that signals attention, compassion, perhaps even respect, is understandable. But the messy, complex and painful work required won’t come from hitting “shift” on a keyboard. The shift comes from confronting uncomfortable truths.

There are some news leaders who, recognizing what this moment requires, are looking beyond semantics and getting to the substance. Marty Baron, the acclaimed executive editor of The Washington Post, announced a new top editorial role and nearly a dozen newsroom slots all dedicated to coverage of race and identity.Baron, whose paper is keeping the lower-case “b” if you are curious, is also grappling with a newsroom challenging his leadership on internal matters related to race (including coverage, decision-making and staffing). But the Post’s moves to bolster its institutional resources on reporting about race and identity stand out nonetheless at a moment when I dare say too many editors — many facing the economic travail wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic — don’t want to entertain the question of how their institutions will change to meet this moment in history.

The “b” debate and the deeper questions confronting the journalism world didn’t begin with these protests or Black Lives Matter. W.E.B. DuBois launched a letter-writing campaign in the early 20th century advocating for capitalizing the “n” in “Negro.”Lack of institutional diversity in news outlets and its role in determining which stories get told and how has been with us for centuries.

I’ve worked as a journalist at The Baltimore Sun, Business Week and was a member of the inaugural reporting class of USA Today, where I covered a number of beats, including civil rights. After leaving USA Today, I served as minority affairs director for what was once called the American Society of Newspaper Editors (now the News Leaders Association after merging with another organization), with oversight of its annual newsroom employment survey that measured progress towards diversity.I successfully argued the results along with the newspaper names be made public. The pushback from some editors brought compromise — an option for confidentiality.The balance of my 40 years in the industry was on the business side of preeminent newspapers and news sites. In positions with several major and diverse metropolitan markets, I inherited from predecessors all-White sales departments, an all-White and all-male marketing team and all-White digital teams.

Like too few successful Black peers before me, I reached the rank of publisher in part for my ability to remedy those and other legacies of the industry’s marred racial past by hiring, developing and leading business teams with the broadest degree of differences possible.

Changing the “b” doesn’t do the painstaking work of changing an institution from the inside.It doesn’t invest in in-depth reporting about the lives of Black Americans or what our anguished communities — through collective memory and trauma — have been asserting for decades, until finally it erupted into the Black Lives Matter movement.Commentators and historians have compared the upheaval of protest in 2020 to 1968, but there’s a key point most haven’t mentioned. An entire generation of pioneering and legendary African American journalists got into newsrooms only because of the turbulent 1960s. The damning 1968 Kerner Commission report indicted the news industry’s hiring practices for not reflecting the demographic composition of the communities they served.

The report cited “white racism” in the form of bad policing, a flawed justice system and voter suppression, among other institutionalized forms of discrimination converged to spark the unrest. It’s withering critique of the media concluded it failed to adequately cover issues of race and reported the news “with white men’s eyes and white perspective.”

While progress has been made, it is difficult to escape the tragic irony of a 52-year-old report, the causes of today’s protests and the media’s still insufficient coverage to bring historical context and meaning to these events.I love newspapers and journalists and it gives me no pleasure to say certain attacks from the far right about the liberal bias and elitism in mainstream media aren’t entirely inaccurate. One former colleague joked that his newsroom’s definition of “diversity” meant hiring someone who attended a public university.

Ask almost any Black journalist how often their ability to fairly report a story was questioned because of their race. Ask the same question of a White journalist. For the ones I’ve asked, it never occurred to them or their editors that was even a question to pose.Among the essential survival skills for successfully navigating and effectively influencing overwhelmingly White newsrooms with its oftentimes blatant and subtle biases, many African American journalists honed the discipline of attacking poor journalism as a proxy fight for challenging White privilege, hubris and bias.

My journalism mentors — Jay T. Harris at Gannett and USA Today; DeWayne Wickham, The Baltimore Sun, Karen Aileen Howze, USA Today; taught me and legions more if you as an individual attacked racial injustice head-on in the form of addressing pay inequities, pushing back against less favorable story and beat assignments, or challenging the running, pejorative narrative on black communities — you became the target. Fight, they taught us, but always make the fight about the journalism.So, let’s do that, by improving the way journalism is done and who is doing it so it’s not about the individual arguing for change, but the institutions committing to making them happen.For substantive change to occur inside newsrooms, the majority of news executives have to come to terms with their organizations’ history in perpetuating inequality and their avoidance of a searing self-examination that would truly lead to dismantling the artifacts of that history. They must do to and for themselves what newsrooms have done for hundreds of years — hold the powerful to account.

These are the newsroom discussions not only worth having, but are required for real progress within the industry and for our democracy.