From K-pop stars to Beyoncé, the issue of colourism remains rife in the music industry

By Ellen E Jones

First Published: Sat 13 Jul 2019

It seems every conversation about colourism in pop music must come back to Beyoncé. So it was when Mathew Knowles, record exec, former Destiny’s Child manager and Beyoncé’s father, appeared on SiriusXM radio to discuss research by Texas Southern University, where he is a visiting professor. Their study found that over a 15-year period it was lighter-skinned black women – the likes of Alicia Keys, Rihanna, Nicki Minaj, Mariah Carey and, of course, Beyoncé – who dominated Top 40 airplay. When asked how different Beyoncé’s career would have been had she been darker-skinned, Knowles was unequivocal: “I think it would’ve affected her success.”

Indeed, Beyoncé descends, via her mother’s line, from Louisiana’s “Creoles of color” or “gens de couleur libres”, a distinct ethnic group in 17th- and 18th-century America, who developed from unions between Europeans and Africans and held privileged positions in society, relative to enslaved Africans. Beyoncé celebrated this heritage on her track Formation, and while Creoles of colour lost their favourable social status from the early 19th century onwards, a shade-based caste system, with whiteness at its apex, persists to this day.

That historical context seems to have been lost, however, in some contemporary music industry conversations, which reframe the issue as the light-skinned star’s struggle for acceptance. “There’s colourism involved in the black community, which is very apparent,” said R&B-pop singer Tinashe in 2017. “It’s about trying to find a balance where I’m a mixed woman, and sometimes I feel like I don’t fully fit into the black community; they don’t fully accept me, even though I see myself as a black woman.”

‘Pretty privilege has worked all through history’: Jorja Smith.

Or there’s a 2018 Beats 1 interview in which mixed-race Jorja Smith expresses the difficulty she has reconciling the notion that she may have benefited from “pretty privilege” in her career with her lived experience of being bullied in a “majority white” school. “There was some ‘Jorja Smith v Colourism’ debate, and I understand, I get it, I’m a conversation-starter. It’s fine … Like I say, people are always going to say something … [At school] y’know, my friends were blond and skinny and had long hair, I had these huge extensions because I just didn’t think I fitted in. People picked on me about it all the time. But, y’know, pretty privilege has worked all through history.”

So you’d be forgiven for assuming that Identity Crisis, the new colourism-confronting pop single by light-skinned Dominican-Brazilian Jarina De Marco, would be more of the same. In fact, the song takes a step back to offer some structural analysis of the issue. With lyrics such as “Marry fair / Stay out of the sun / Bleach your skin / Isn’t this fun?”, De Marco satirises how white supremacist beauty standards are passed down by the cosmetics industry and within our own families.

“Look at someone like Beyoncé,” says Lao Ra, a Colombia-born, UK-based pop singer, who appears in Identity Crisis’s accompanying short film, Conversations on Colourism. “Don’t get me wrong, she’s a talent like no other, but her physical appearance perhaps played a small role in her initial mainstream appeal.”

Like De Marco, Lao Ra also acknowledges her own light-skinned privilege. “Perhaps I have the right amount of ‘exoticism’. It plays in my favour, I suppose, but in the major scheme of things it sucks that relatability comes from how light or dark you are rather than the music you’re making.”

This openness remains unusual in the music industry, where commercial considerations seem to make pop stars in particular prone to adopting society’s prejudices. And colourism isn’t only a thing within the African diaspora. This kind of intra-community discrimination is big in Korea too, says Aimee Allport, a British-born language tutor and K-pop fan, who lives in east Asia. “The everyday Korean is very interested in the beauty standards that are set by idols [K-pop stars], such as their weight and, of course, their skin colour.”

There are a handful of artists of mixed African-American and Korean heritage who have made Korean-language songs about racism, such as rapper Yoon Mi-rae’s Black Happiness, but colourism is much more widely practised and much less openly challenged. Witness the numerous YouTube clips of boybands EXO and BTS teasing supposedly darker members or pointedly applying high-factor sun cream. Allport points out that darker-skinned K-pop stars are also often stereotyped as “sexy” in comparison to their “cute, doll-like” paler counterparts, citing the example of Hyolyn from Sistar, who is known as “the Korean Beyoncé”.

One thing common to colourism in all these guises is a disproportionate impact on female artists and fans. The tradition of “lighties”, “yellowbones” or “light-skinned tings” being objects of desire and status symbols in the music videos of male artists runs across pop genres – a situation that can be as demeaning for the fetishised as it is for the ignored. In a December 2006 interview with Essence magazine, Kanye West is quoted as saying: “If it wasn’t for race mixing there’d be no video girls. Me and most of our friends like mutts a lot. Yeah, in the hood they call ’em mutts.”

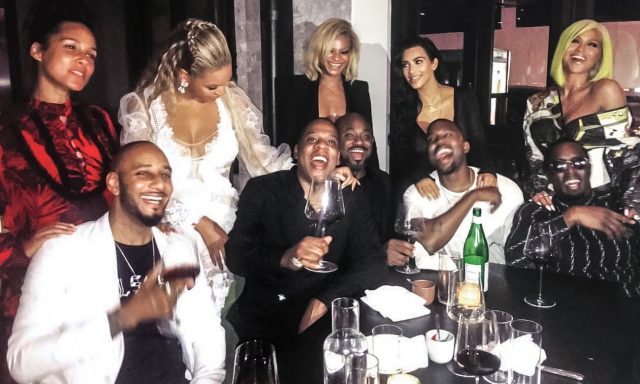

If you assumed attitudes must have matured since, you’d have been disappointed by a 2016 Yeezy fashion show casting call that requested “multiracial women only” and by that now-infamous post-VMAs photo from the same year. It featured some of the most powerful men in entertainment (Swizz Beatz, Jay-Z, Steve Stoute, Kanye West, Sean “Diddy” Combs) sitting down to a post-VMAs drink with their light-skinned or non-black significant others standing dutifully behind them (Alicia Keys, Beyoncé again, Lauren Branche, Kim Kardashian-West and Cassie). It’s as if they’d chosen to have their photo taken right at the intersection of colourism and sexism, like tourists posing under the Welcome to Las Vegas sign.

Beyoncé Knowles, Kelly Rowland and Michelle Williams of Destiny’s Child. Photograph: KMazur/WireImage for People Magazine

Around 2011, this all became a bit much for UK grime artist Lioness. “I stopped creating music for about six years, and in that time I constantly saw, on social media, dark-skinned women being the topic of banter from – most commonly – dark-skinned men,” she says. “Part of the reason I left the industry was because of comments from A&Rs about my complexion … It wasn’t in their interests to go against the believed wisdom within the industry that the general public wouldn’t buy into a dark-skinned female.”

When Lioness did make her comeback, it was with a renewed determination to tell the truth about this industry-wide issue. Her 2018 release DBT (Dead Black Ting) Remix brought together a melanin-magnificent lineup of female MCs: Queenie, Stush, Shystie, Lady Leshurr and Little Simz. Lioness’s new project, Overdraft, comes out in October and she says she has “absolutely” noticed an industry change in the meantime.

“We have dark-skinned males now making songs that broach the topic. The dark-skinned male has always been accepted within the music industry, so when he now speaks on colourism, it’s monumental. When it comes from black women themselves, however, it’s unfortunately seen by the masses as another complaint. The Angry Black Female strikes again.”

Lioness specifically points to two recent releases: the shining beacon of paternal pride that is Ghetts’s Black Rose and the sultry, summery desire of Che Lingo’s Black Girl Magic. Further afield, there’s also Black Hypocrisy by Jamaican dancehall artist Spice and Kendrick Lamar’s Complexion (A Zulu Love). Beyoncé’s great – we all stan Beyoncé – but if Beyoncé is the only shade that’s celebrated, then the whole world is missing out. “I’m glad I took time out at 22 years old, to thicken my skin and realise my worth,” says Lioness. “In 2019, I accept any challenge where my complexion is concerned!”

Source: Guardian.com